“We are moving from a world where computer power was scarce to a place where it now is almost limitless and where the true scarce commodity is increasingly human attention.” Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft

“We are moving from a world where computer power was scarce to a place where it now is almost limitless and where the true scarce commodity is increasingly human attention.” Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft

It’s almost a truism that our attention spans are dwindling. What does that mean for writers?

First, let’s get our minds around the issue – starting with the goldfish myth.

The Great Goldfish Myth

In the spring of 2015, The Consumer Insights group of Microsoft Canada published a report entitled “Attention Spans.” The report, for a marketing audience, included the quote from Nadella reinforcing what many of us feel: attention is the new currency.

Coming from a technology marketing background, I understand how these research reports work. Marketer researchers gather interesting insights and package them to meet the objectives of the organization funding the research. This isn’t the theory-testing type of research that advances science. Take these marketing-focused research reports with a healthy grain of salt.

This particular report generated a larger wake of online responses than its origins would suggest. The media was on a salt-free diet when it came to this report. (Sorry, couldn’t resist.)

Major news organizations, including Time Magazine, jumped on the findings – specifically, the idea that the dwindling human attention span is now less than that of a goldfish.

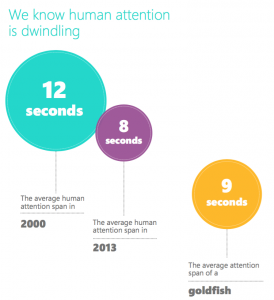

The goldfish takeaway came from one simple graphic in the report showing three bubbles:

- A large bubble representing the average human attention span in 2000 as 12 seconds

- A much smaller one showing that same attention span shrank to 8 seconds (I’m not convinced that the proportionality of the bubbles is correct)

- A third bubble between the two representing the 9-second attention span of the average goldfish

Unfortunately, none of that data comes from the actual research in the report. A little digging reveals that the data originates from a self-reported survey of 2000 Canadians, as well as a bit of research hooking up 110 people to electrodes. (Again, no goldfish.)

This is not a peer-reviewed research journal. Yet the mainstream media jumped on it like hungry koi at feeding time.

Saner voices debunked the headlines after a while.

Like all good Internet memes and urban legends, the idea of our sub-goldfish attention span lives on. It still appears occasionally in materials for marketers, who are not known for rigorous vetting of sources.

The Real Proof Is Found in the Persistence of the Myth

The spread of this comparison illustrates the very thing that the researchers were studying: our attention spans. The popularity of the goldfish idea reflects three core truths:

- Sometimes we look at the pictures and don’t read the text. The bloggers, journalists, and others reporting on the data couldn’t have carefully read report itself. Once you do, its limitations and purpose become clearer.

- Unexpected visual images are powerful. Because we can picture a goldfish, we remember “less than a goldfish” even if it’s not precisely accurate.

- We remember things that confirm our internal experiences. This research simply felt right.

All of us are skimming through online sites and articles, multi-tasking across devices, leaving browser tabs open, and probably doing less focused work than we remember doing in the past. So when we read about our overwhelmed, shortened attention spans, we believe it.

It Might Be True After All

One of the great advances in neurobiology in recent decades has been the idea of neuroplasticity – the ability of the brain to ‘rewire’ itself based on our behavior.

If you’ve seen the study about the London cabbies who study for “The Knowledge” and change their brains, then you know that behavior can affect the pathways in our brains. The more we do something, the more we wire our brains to do that thing.

To use an analogy from an entirely different set of human processes, consider the track athlete. If you specialize in the hurdles and spend all of your time training on sprints and hurdles, you’ll do well when running those events, but your performance on the 10,000 meter race will slip.

Like the hurdler’s training, the track analogy doesn’t get us very far (sorry). Brains are way more complicated than muscles. But like muscles, they respond and remodel themselves based on our behavior. Start doing an unusual task frequently and persistently enough, and you will experience minor chemical changes in the brain to support that activity. Do it even more, and you’ll start hard-wiring the neurons to support that activity.

In other words, your brain at this moment is a creation of not only your genetics and your environment, but also your ongoing actions.

What does this mean to writers?

Writers, Readers, and Attention Spans

Like everything involving human cognition and behavior, attention is complicated.

However, we can the fact that technology is significantly changing our reading environment. We now read things differently than we used to.

In his Pulitzer-Prize nominated book The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, Nicholas Carr argues persuasively that technology is changing the way that we read. He bemoans the loss of “deep reading” in which the reader is absorbed in a text, taking it in at their own pace, without distractions.

When we do sit down to engage in deep reading, we’re unaccustomed to it. It’s more difficult, because our brains are out of shape, having spent so much time doing short bursts of attention switching.

Context matters as well. If you are publishing online text like blog posts, then you’re reaching the reader in a situation in which they expect to be distracted. When they read a book, however, they may dedicate more uninterrupted time to reading. Maybe.

This post, for example, is probably too long and detailed for many blog readers, especially those of you reading on phones. Sorry about that.

Take-aways for Writers

- Technology is changing the ways that readers consume information and news, and those changes are both rapid and pervasive.

- More things are competing for your readers’ attention than ever before. Some people are more selective about what they will spend time reading.

- Technology presents more multitasking opportunities when people are reading.

- When writing for the distracted reader, make it easy for people to find the key point, and to leave and return to the work. Use subheads for navigation. Repeat yourself if necessary.

Finally, remember this: some of the online panic about shrinking attention spans comes from media businesses that make their living on owning or claiming that attention.

Remember the Microsoft study about attention spans? It was written for marketers and advertisers — the people most likely to interrupt your reading and grab your attention. Protect your attention and evaluate your sources.

Related Posts

Books for Writers: The Shallows

Battling Distraction When Writing