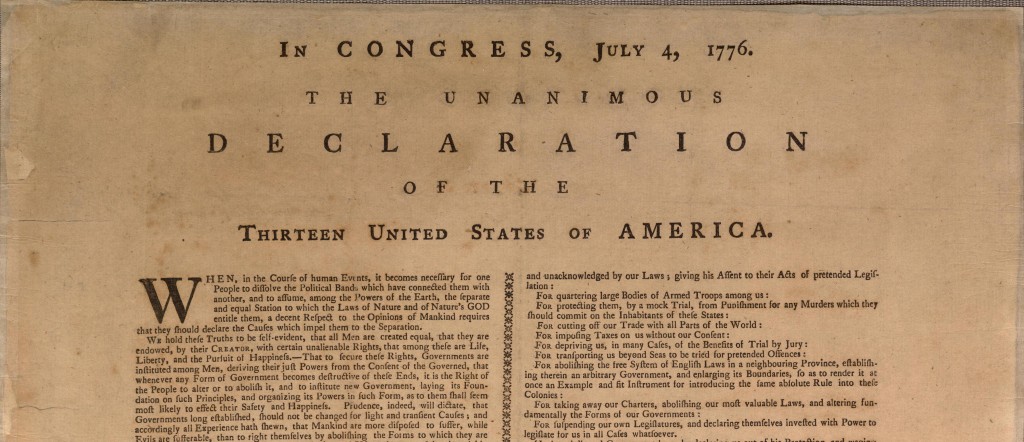

Many people know that Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence. You may not realize that other members of Congress edited it.

Imagine sending your carefully crafted draft to the United States Congress for revision.

When comparing Jefferson’s first draft to the final, it’s clear that many changes led to substantive improvements. That’s what happens when Benjamin Franklin and John Adams are on your team. Never undervalue a great editor.

(You can compare the rough draft and the edited version online at www.ushistory.org/declaration/document/compare.html.)

But what happens when you have multiple people involved in reviews, including people who are not editors in their day jobs? I’m referring to the corporate writing environment, in which colleagues, managers, partner organizations, and legal teams can weigh in on your text.

I once wrote a press release about a technology partnership for a company I worked with. As it was to be a “joint” press release, the partner company’s legal department had to sign off. Instead, the legal team rewrote the release entirely, changing not only the content but the descriptions of the technology. That turned out well…

A more common scenario is this: you get conflicting revision comments, or someone new joins the review and questions the overall direction and purpose of the piece. These situations can drive a writer batty. Worse, they can lead to delays of weeks or even months in getting something published.

A little advanced planning can limit the risks of reviews run amok.

Plan Ahead to Deflect Conflict in the Review

Bypass problems by planning ahead of time.

Get agreement early on the audience, purpose, and style of the piece. Add this information to the outline of the piece, and ask people to sign off on it before you start writing.

When everyone has agreed up front about what you’re trying to do, the revision process entails determining whether or not you have achieved those objectives. People who have agreed to the approach are less likely to derail a project during reviews.

Plan for conflicts. Decide upfront who gets the final editorial say regarding tone and style, and who has the final approval on subject matter.

Clearly define the scope of each review. If you give the piece to a subject-matter expert, explicitly describe the input you need. For example:

- Can you look at the second section and let me know if it’s accurate?

- Have I missed anything that should be included?

Review cycles can spin out of control when software engineers start debating the use of the serial comma. (No one has solved that debate yet.) Make sure people understand what level of response you expect from them.

Deal with Conflict Gracefully When It Happens

Sometimes, despite advanced planning, you end up with conflicts and headaches during reviews. If that happens, you may have to be the one who bends.

Let go of your ego attachment. The people in your workplace may lack the literary skills of Franklin and Adams, but they often bring valuable, relevant perspectives. The author’s role is to care about the work enough to accept edits that make sense, recognize other opinions, and make the writing better.

Become the reader’s advocate. What happens if you get conflicting instructions or disagree strongly with comments coming back at you? Consider the ideal reader and argue for their needs. If people suggest changes that serve readers in the target audience, then respect the work and the readers enough to accept the changes.

Channel your inner Thomas Jefferson, as he sat through a committee editing his lovingly chosen words. If he survived extensive reviews and revisions to what was arguably his most important creation, you can as well.

Related reading

For more thoughts on writing as a team sport, see the book The Workplace Writer’s Process.