Short Version

Short Version

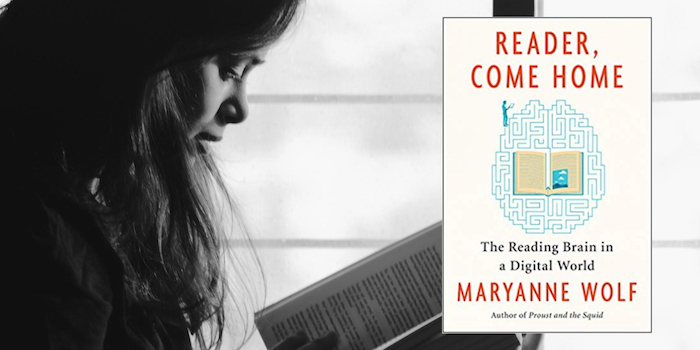

In Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World, Maryanne Wolf makes the argument that the digital world is transforming our reading brains, and not always for the better. Only by understanding these changes can we figure out how to navigate them and form a brighter future for a literate, and digital, society.

(When you read the book, you’ll recognize the irony of leaving a shortened version of the review.)

Long Version

In her latest book, cognitive scientist, literacy advocate, and author Maryanne Wolf suggests that we are in the midst of a transition from a literacy-based culture to a digital one, without necessarily understanding the costs, risks, and cognitive effects of that shift.

Reader, Come Home is Wolf’s personal foray into what that shift means and how we should be thinking about it as parents, teachers, citizens, and readers.

She grounds her argument in cognitive science. We must learn and develop reading as a skill; our brains are not hard-wired for reading, but co-opt a variety of different mental systems into what Wolf refers to as our reading circuit. We train this circuit throughout our education as we learn to read with more depth and analysis. If all goes well, we develop a love of reading and can lose ourselves in a good book.

But there’s one big reason we cannot take this reading ability for granted: neuroplasticity. Much like our muscles, our brains adapt to the activities we use them for. As Wolf writes, the reading circuitry in our brains is influenced by what and how we read. If we spend all of our time skimming through text, impatiently clicking through to the next thing or scanning for the gist and moving on, those are the mental circuits we will reinforce, often at the cost of deep reading capabilities.

As to why this matters, Wolf says it best: “When language and thought atrophy, when complexity wanes and everything becomes more and more the same, we run great risks in society politic—whether from extremists in a religion or a political organization or, less obviously, from advertisers.”

The Book’s Structure

In an appropriate gesture to the literary past, Wolf frames the work as a series of letters. (That’s an epistolary format, for the English majors out there.) This choice lets her speak directly to us as readers, whether we are skimming or deep reading.

Each letter offers a different filter on these essential questions: Is the way that we read changing because of our increasingly digital environment? What does that mean for analytical thought? How can we understand what’s happening, and how should we approach this shift, particularly when it comes to teaching children?

In the second letter/chapter, Wolf describes the “reading circuit” in the brain using the analogy of an elaborately choreographed circus performance like a Cirque du Soleil show. The act of reading engages both hemispheres, multiple lobes, and all of the layers of the brain. While the centers for vision, language, and cognition have the most action, they’re not the entire show. The affective (emotional) and motor systems in our brains are standing by, poised to join in when we encounter an analogy or image that triggers an emotional response. Reading and comprehending is a remarkable feat.

In the chapter describing deep reading, Wolf describes the many cognitive processes that reading develops and supports, including empathy, analogical reasoning, and critical analysis. And in the chapter entitled “What Will Become of the Readers,” Wolf recounts her personal experience of revising a book she had loved earlier in her life—Hesse’s Magister Ludi—only to find that she could not tolerate reading it. In the course of researching, thinking about, and teaching reading skills, her own deep reading abilities had diminished. She had to retrain her own deep reading capabilities.

If it can happen to her, it can happen to anyone. Take care.

In chapters focused on parents and educators, Wolf offers sound advice for raising literate children adept at both deep reading and navigating the digital world by finding a happy balance and making a planned transition to digital forms. Spoiler alert: keep reading those physical books to young children!

Key Take-Aways

This book spoke to me on many levels.

As a cognitive science geek, I loved Wolf’s descriptions of the mental processes of reading.

As a nonfiction writer, I was particularly taken with the research on how much information we are all subjected to on a daily basis. Wolf cites studies suggesting that the average person encounters 100,000 words a day; clearly skimming is our only defense. That’s why it’s so critical, when you’re creating marketing or business content, to support that skimming reader, rather than counting on the efforts of a focused, deliberate reader.

As a lifelong reader, I mourned the reduction of deep reading in my own life, and resolved to do something about it—starting with this book. I slowed down, took notes on the neuroscience, and savored the prose, like the following:

“How we reckon with the time we are given—in milliseconds, hours, and days—may well be the most important thing any of us chooses in an age of continuous flux.”

Reading this book has made me resolve to protect my deep reading time, and keep training those neural circuits.

Other Related Reviews

Books for Writers: The Shallows by Nicholas Carr

For advice on writing to reach that distracted reader, see my book Writing to Be Understood: What Works and Why.